News

An Unexpected Trip to Cambodia, October 2018: Recovery of Ancestral Knowledge and Ways of Life

By Fernando Quilaqueo Calfuqueo

Field Coordinator for MAPLE Microdevelopment Chile

Member of the Llaguepulli Mapuche Community

January 2018

Translated and Edited by Teodora C. Hasegan, Anthropologist, Ph.D.

Original Spanish Version: Click Here

Please also enjoy our most recent video field update featuring Fernando by clicking here!

An unexpected invitation…

It was to our honor and delight that the PAWANKA Foundation sent an invitation to the Community of Llaguepulli to participate in a gathering of Indigenous leaders from several pockets of our planet...in Cambodia! I had never been to Cambodia before, or that part of Asia. Cambodia is a small country in Asia, with a population similar in terms of size to that of Chile, but very different socially, economically and culturally from Chile.

My community were recipients of a grant for the first time awarded in 2017 by the Pawanka Foundation (supported by the Indigenous Ways of Knowing and Learning, an indigenous-led grant-making initiative) to help us transition to a healthier agriculture, by re-linking our native seeds and ancestral knowledge. With the support of MAPLE Microdevelopment Chile and together with two more members, Fresia Painefil and Kelv Painefil, I participated at the gathering in Cambodia as a representative appointed by the leaders of the community and as a member of the management team of MAPLE Microdevelopment Chile’s program for transition to agroecology.

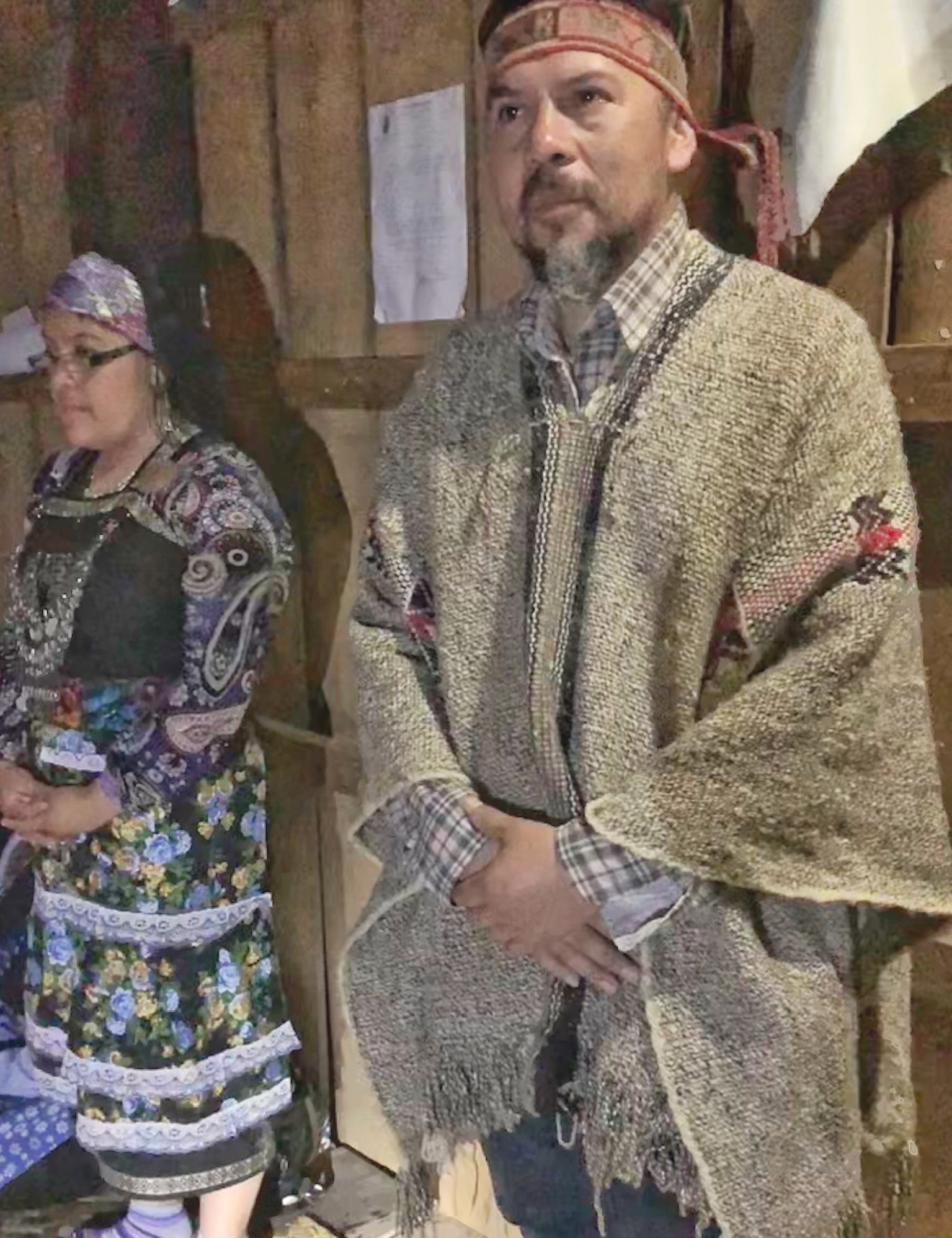

Photo 1. The delegation to Cambodia with members from the Mapuche community of Llaguepulli: Fernando Quilaqueo (center), Kelv Painefil (to his left), and Fresia Painefil (second from right), October 2018.

The Objectives of the Trip

The purpose of this trip was to participate in the Regional Exchange of Learning about Seeds, Food Security and Agroecology meeting held between October 22 and 26, 2018 in the city of Siem Reap in Cambodia. This meeting was organized and funded by the PAWANKA Foundation and the Organization for the Promotion of the KUI Culture of the Preah Wijía Province of Cambodia, and represented an occasion for past grantees to share experiences of their community initiatives. It was an opportunity for us First Peoples Communities to discuss projects we have implemented and developed on the recovery of ancestral knowledge (especially related to seeds) and ways of life (based on the relation between human beings and nature). The gathering had a gender and holistic approach in the context of climate change. Indigenous women were convoked to speak about holistic agricultural solutions in their communities such as organic agriculture and safeguarding of native foods.

Some of the Communities and institutions that participated were: the host, the Organization for the Promotion of the Kui Culture of the Province of Preah Wijía in Cambodia (OPKC); Trinamul Unnayan Sangstha from Bangladesh (TUS); Mizquito community from Nicaragua; and the Mapuche Community of Llaguepulli from Chile, Joan Carlin (Pawanka Foundation Director), Mariana López (Pawanka Foundation Coordinator), Karla Busch (Pawanka Foundation Executive), and Yuri Futamura and Alan Zulch (from the TAMALPAIS Foundation) (headquartered in San Rafael California), main donors of PAWANKA funds, also participated.

What We Learned from the Gathering

Among the main experiences and lessons shared by the participating Communities in this meeting I should highlight the similarity in the processes of social, cultural, and economic changes caused by colonization and state policies. There is also an incessant struggle for self-determination and conservation of natural resources, which are threatened mainly by timber and monoculture industries, especially in Cambodia and Bangladesh.

But I remember also the successful experience of collaborative relations between the Kui Community, through the elders’ council, and the local police and the province. Jointly and through a strategic plan, they work to protect their native forest already restored and managed by the Kui Community itself. This would be inconceivable even in Wallmapu (a Mapuche ancestral territory), where the police have very different interests than the defense of collective rights.

International Allies to Indigenous Peoples

International allies are key for creating support to First Peoples striving for a better Planet. For example, the collaborative approach of our international allies in the territory is to install and develop tools or self-management capabilities in the Communities with regard to natural resources and family economy which are in accordance with the natural cycles or Mapuche Lafquenche worldview. Our great challenge in the medium and long- term is to consolidate a self-management team in the Community to lead our own development proposals, and become ever more autonomous in the decision-making processes while strengthening our youth to become the future leaders of our communities and family economies.

I learned that the Kui Community, especially, maintains its cultural traditions intact. Its relationship with forests is of vital importance for its economy and families because the tropical forest has a great biodiversity of species which constitute the main source of nutrition for families, in addition to providing wood, harvesting resin, fish and livestock.

Collectively, the Community grows traditional organic crops of rice, tubers, corn and beans, many of them using their own traditional seeds, incorporating techniques in rotation management and association of crops. The forest soils are very fertile and have a productive cycle because the tropical climate with two seasons (winter and summer) allows them to have up to two annual harvests and an abundant availability of water resources throughout the year. Each family home in the Community owns a small garden for vegetables and tropical fruits, such as: coconut, bananas, mangoes, dragon fruit, jackfruit, etc.

On the other hand, in our territory, due to a temperate climate with very different seasons, the cultivation systems are very different, with annual harvests, so the production cycle is less dynamic. At the same time however, both Kui and Mapuche cultures are similar in their respect for the holistic sense of care for seeds, land and biodiversity.

Photo 2. Fresia Painefil and Fernando Quilaqueo, from the Llaguepulli Community

Vision for the Future

Currently, I am developing a collaborative work plan in the Community of Llaguepulli with MAPLE Microdevelopment Chile as part of the community management team. This involves, on one hand, supporting 12 families that are in the process of agroecological transition, by strengthening their crops of quinoa, native potatoes, vegetables and fruits through the recovery of seeds of local ecotypes, without agro-toxic products. On the other hand, we are working on a community proposal complementary to the previous one and which relates to the revaluation of our environmental assets. These are fundamental for transition, soil recovery, wetlands, and, through agroforestry, are linked to our community nursery. Since its setting-up, this nursery already has a permanent stock of annual production of species native to the area, aiming at restoring the community and the territory.

The Community of Llaguepulli, culturally very active, is a point of national reference in developing models of self-management in community tourism, intercultural education, and community bank (Mutual Support). The vision for the future is to also be a reference point for the restoration and conservation of community food and environmental heritage.

Conclusions

One of the best experiences at this event was, without a doubt, sharing about our agro-ecological transition and restoration program in the Community of Llaguepulli. Also special for me, as a Field Coordinator member of MAPLE Microdevelopment Chile and member of this Community, was to witness the efforts to strengthen the Kume Monguen (good living) in other places.

Today, as always, Indigenous Peoples need assistance to carry out their proposals with an endogenous perspective according to their own needs, especially in critical areas, such as recovery of environmental assets, which is closely related to strengthening the social structure of our people.

The training of young leaders empowered with tools for community self-management and with a gender approach is the vision of institutions such as MAPLE Microdevelopment Chile and PAWANKA to achieve a holistic and integral development in our Communities. This is why PAWANKA has decided to continue to finance this year our program for strengthening the economy and nutrition of our families, in order to empower the community management team. We appreciate both MAPLE Microdevelopment Chile and PAWANKA for their trust in us and the opportunity to undertake this great challenge.

Finally, I would like to thank all those who made possible this important experience: the entire community management team at MAPLE Microdevelopment Chile, my family, Community, and PAWANKA.

Llaguepulli, Pewü (Spring) 2018

Photo 3. Cambodia

Photos by Alan Zulch, Tamalpais Trust

The Emergence of the Lafkenche Tree Nurseries for Lake Budi’s Eco-cultural Biodiversity

By Ignacio Krell Rivera, M.A. in Environmental Studies

Translated and Edited by Teodora C. Hasegan, PhD in Anthropology

Author´s Note: As an environmental sociologist working with Mapuche communities and leaders for 20 years, in this blog post, I aim to provide information as well as a few conceptual frameworks to interested readers and supporters so we can understand why a simple project such a community tree nursery network, can have a major impact in regenerating, not only endemic temperate forests and coastal marshlands, but also the indigenous Lafkenche (People of the Sea) eco-cultural knowledge as well as a more balanced economy with a stronger role of indigenous communities, families and women. (Para una versión en español haga click acá.)

Please also enjoy a small clip featuring this collaborative effort available at MAPLE’s youtube channel by clicking here!

Thank you,

Ignacio Krell Rivera, November 2018, La Araucanía, Chile

Soil erosion and socio-environmental vulnerability in Lafkenche Lands of Northern Patagonia

The erosion of soils and the degradation of other environmental resources fundamental to rural life and production—such as water, eco-cultural biodiversity, aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems—and the resulting devaluation of agriculture in general, and the small indigenous agriculture in particular, are global phenomena that affected Araucanía region of Northern Patagonia severely, with 28.6% of its soils eroded (CIREN 2010) and the higher rates of rurality and poverty in Chile, a mid-level income but highly unequal country.

In the Araucanía region, an enormous and once fertile section of the northern Patagonia in south-central Chile, and broadly speaking, the historic territory of the Mapuche indigenous nation, this severe damage of soils and other natural resources is the product of a chain of processes triggered by violent colonization of the ancestral and previously autonomous country of the Mapuche (People of the Land) in the late 19th and early 20th century, not long ago covered by a thick mantle of endemic temperate forest.

Lake Budi

According to a report by Universidad Mayor (2011), the main socio-environmental threats for Lake Budi, the ancestral territory of the Lafkenche (People of the Sea) —an Indigenous Development Area (ADI) since 1996, whose mega-diverse wetlands were also declared Priority Conservation Site in 2002 are: “a) Soil erosion and degradation, which increase when developing practices that do not take into account the capacity of the land use and the size of the property; b) Loss of biodiversity” (U. Mayor 2011, p. 6).

As in many of the Araucania Region’s basins, the aforementioned historical causes of environmental degradation were triggered by the late extractive colonization of the area, in this case, by the timber enterprise “Budi Colonization Company”, as well as the so called “reduction” of its indigenous inhabitants -a term used in the late 19th century to describe the displacement and forced settlement of Mapuche indigenous families in small plots in coastal areas with steep slopes. This “reduction” of the Lafkenche communities and their resource base was followed, by mid 20th century, by the gradual fragmentation of remaining indigenous lands and the adoption by small Lafkenche farmers of state-promoted but inadequate cultivation and intensification practices with chemical inputs (Mariola 2018). To this day, the pressure of productive and subsistence activities on forests, soils, waters, ecosystems, the action of wind and water on exposed surfaces, slopes and banks; and the cumulative impacts of the massive introduction of exotic forest monocultures with high water demand, have caused almost irreversible deforestation and fragmentation of the ecosystems in the Budi basin, with the consequent losses on the quality of soils, water and biodiversity over the entire basin (Peña Cortes 2006, University of Chile 2010).

This widespread environmental degradation of indigenous lands of Lake Budi, limits their uses in sustainable family and community businesses such as tourism, organic agriculture, valorization of berries and native foods, and even traditional activities, such as grazing and the cultivation of grain and potatoes. This negatively affects the economies of its 15 thousand inhabitants, grouped in 120 Indigenous Communities and dedicated mostly to subsistence agriculture, family tourism and crafts.

In Budi, entwined historical trends of degradation of environmental resources and socio-environmental vulnerability continue to heavily impact a new generation of Mapuche-Lafkenche, who is massively out-migrating in search of economic opportunities or sometimes just temporal sustenance in big farms –endangering also linguistic and cultural intergenerational transmission.

The recovery of introfillmongén

Introfillmonguén can be broadly translated from Mapudungun as “Eco-cultural biodiversity” –literally, all interconnected life. Currently, MAPLE Microdevelopment Chile works with three Indigenous Communities: Malalwe-Chanko, Allipen, and Llaguepulli -all in the municipality of Teodoro Schmidt and within the ADI Budi. In collaboration with multiple actors, these Communities are developing alternatives to conventional agriculture, such as cultural tourism, and crop cultivation, processing and cooking native organic foods, gaining national and international notoriety.

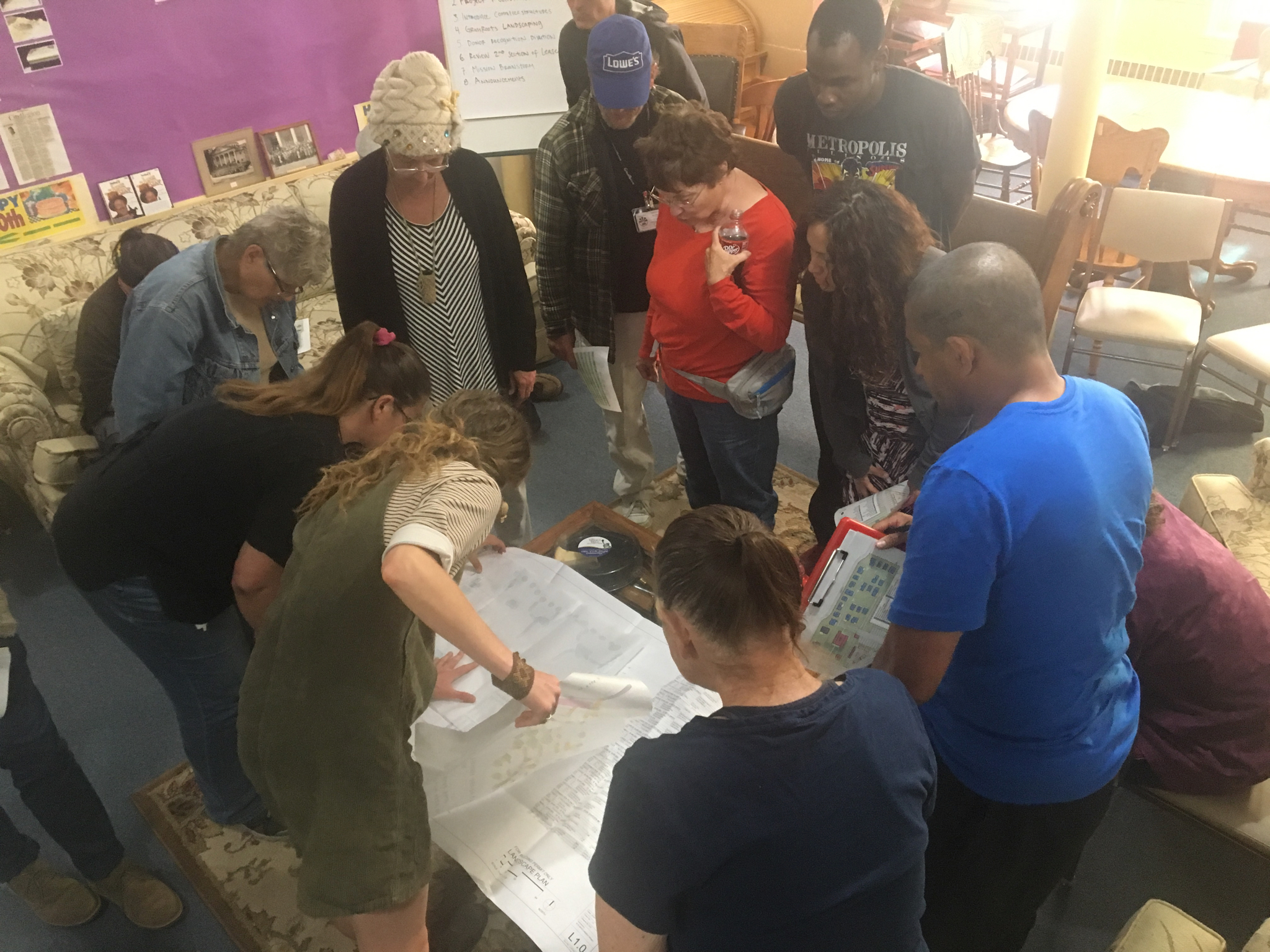

With support from MAPLE Chile, these communities, together with an interdisciplinary team and partners through programs with national and international funds, and have learned that by incorporating native and multipurpose trees into their land they allow the recuperation of ecosystems and environmental assets and services that add value to degraded lands while improving the environmental quality of the basin and its water systems, fisheries and bio-cultural resources, such as the endangered indigenous knowledge of herbal medicine. These three Lafkenche Communities, using small grants from the Environmental Protection Fund of the Ministry of the Environment (FPA-MMA) and international projects, and supported by the National Forest Corporation(CONAF), the National Institute of Agricultural Research (INIA), and the local Municipality, have already set up their own small native and fruit tree nurseries, have trained working teams with technical and managerial skills, and now seek to co-design an associative strategy to achieve sustainability, impact and scale. And, through joint training workshops and community- to- community exchanges of learning, information and genetic material (seeds and clones), these three communities have also established a basis for now building a network of community nurseries to effectively address the integral environmental management of the basin.

Community leaders working with the MAPLE Chile team and other allies, have realized that adding to the aforementioned historical factors of environmental degradation, there is a gap in the supply of native and multipurpose species by public and private entities in the area, and a lack of incentives and collaborative methodologies that could involve small indigenous owners in incorporating these species into their lands and economies are foreclosing the chances of Lafeknche communities to curve the damage by re-incorporating a biodiverse vegetal cover. We have found, for instance, that of the 250 registered commercial nurseries in the Araucanía region, only 15 are located within the 5 coastal municipalities—these being some of the most affected by deforestation, erosion and socio-environmental vulnerability—and of these nurseries, only 2 produce native or fruit trees (Source: SAG Registry of Nurseries).

The Lafkenche Nurseries’ Network will address this gap as:

1. Community nurseries can be engines for reforestation and regeneration of environmental assets throughout the basin, encouraging the incorporation of biodiverse vegetation cover by offering incentives through a locally relevant offer, at a low cost;

2. These community nurseries, through an associative strategy, can become economically sustainable while generating a surplus, which can be invested in promoting social and environmental objectives of the associated communities.

In sum, the Nursery Network for Itrofillmonguén (or eco-cultural biodiversity) of Lake Budi can become a Lafkenche environmental self-management model with potential to regenerate the Budi’s itrofillmonguen, currently under threat, by stopping the chain of consequences of extraction and marginalization, while re-valorizing indigenous properties and restoring the resources of the basin, enhancing their tourism and agro-ecological potential, in a sustainable way and with full participation and self-governance of between 3 to 120 communities of ADI Budi.

MAPLE helps setting up an Indigenous Tree Nursery Network based on the needs and capacities of the communities in the Budi basin territory

The role of MAPLE Microdevelopment, the main partner of this project, is to co-create capacities, work teams, and appropriate, low-cost tools and methods to promote from within the communities themselves the environmentally, socially and financially sustainable development of the basin. Fernando Quilaqueo, a community-based agro-ecologist and MAPLE’s field coordinator, explains:

“The tools and techniques that we have developed for some years in the context of our community environmental restoration program we have called Liftuayiñ taiñ Lewfu, were first implemented in the Allipen Community, and later replicated by the Llaguepulli and the Malalwe-Chanko Communities. Each planting season we have been able to encourage a number of families (currently at 60) to enclose spaces within their farms to plant native species such as Maiten, Notro, Maqui, Pilo pilo, Hualle, to establish a multipurpose tree curtains, buffering Menoko (natural springs) and wetlands, as well as the re-establishment of woodlands in eroded slopes either through contour lines and hillside infiltration ditches. From the initial implementation of these agroforestry techniques, we have seen a huge advance, both in the valuation of natural and human resources and in the progress in the restoration of our territory. So far we have planted more than 5000 native trees, and now that we have our own community nurseries for the production of native or multi-purpose plants which are of great interest for our communities’ restoration plan, we can hope for long-term positive impact on our territory, the Budi basin.”

Our team taking a walk in the Allipen Community: Tree lines created to recover environmental assets can be observed.

MAPLE and our community partners and collaborators are also developing a focus on the role of women and youth in the propagation, cultivation, and value addition of native berries such as murta (ugni molinae) and maqui (aristotelia chilensis). Lamngen (Sister) Olga, one of two women in charge of Allipén’s Tree Nursery who has been participating in capacity building processes since 2016, says that, for her, being responsible for the project, “it is a pride, in the first place, and I want to thank the Community and those who are supporting us for having set up this nursery, because we had never thought of having a nursery here... so close, so close to my home. We started with little, we did not know anything, and we have learned a lot.”

Reflecting on the broader issues connecting this project with identity, environment, and economies, Olga adds: “The plants that are native, that our own, of Mother Earth itself, are disappearing. They are now only replanting eucalyptus and pines, and we are no longer seeing native plants in our lands. With my family, we are well now in that sense, because we can have these murta plants” Lamngen Juanita, her co-worker in the nursery project, adds in relation tu the propagation and reincorporation to the murta o üngi native berries (ugni molinae) to Lafkenche lands and economies: “The murta is a red berry from which you can make jams and desserts, and perhaps other things we have yet to learn: I’ve heard one can make really good ice cream with it!”

The pilot murta berry garden installed in the Allipen Community in 2016

During 2017, the first nursery installed in 2015 was able to deliver plants locally to the aforementioned collaborative regenerative effort donating species, valued at 1 million pesos, to members of the community, and reaching sales of about 200 thousand pesos to individuals, which allowed to cover some operational costs. Thus, 80 families affiliated with 3 Indigenous Communities are already benefiting from the environmental impacts associated with access to a supply of native and multipurpose plants, locally relevant, biodiverse and at low cost. Each greenhouse also generates 2 jobs, directly benefiting 6 local families with training and stable and dignified work. Moreover, the inventory of the 3 nurseries continues to grow, in number and diversity, and the communities, with the guidance of external assistants, are seizing the opportunity to sustain the operation of their nurseries through the associative marketing of a part of the production, thus preventing programs from being closed down due to the lack of external support for the managers.

All these community-owned assets and capacities offer today a strong base for an Indigenous-managed, self-sustainable model of territorial regeneration. From now on, the challenge will be to agree on and implement adaptive strategies to explore the potential of this Lafkenche endogenous proposal for indigenous-controlled eco-social regeneration which can have the following and crucial advantages with respect to the offers and proposals coming from the dominant Chilean society:

1. It generates exchange, income and promotes self-financing, so it does not depend on external subsidies beyond the initial phases of installation and incubation; on the contrary, it may generate income, community assets, and employment, in a sustainable, environmental, social, and financial manner.

2. It generates a local offer of trees, biodiverse, culturally relevant and at a low cost, addressed to the local communities, which can also be subsidized with the income produced by commercial operations.

3. Stimulates local participation by generating levels of trust, flexibility, and adaptability unprecedented in “top-down” programs, by respecting and implementing cultural protocols and recognizing the role of the Mapuche people’s own authorities through relevant mechanisms of decision-making and self-governance.

4. It opens spaces for the global dialogue on ecological knowledge, by stimulating cross-cultural collaboration by scientists and Mapuche wise men and women to co-generate knowledge as well as physical reserves of genetic resources (seeds and species of plants, shrubs, and native trees) essential for its restoration of the territory.

Replicability and scalability are at the heart of the model, which originates in the association of 3 Communities that work together to raise the quality and volume of supply and thus achieve sustainability. In the short-term, the model allows the incorporation of more nurseries within the ADI Budi where the Network and its main ally, MAPLE Microdevelopment Chile, will be able to support the creation of new nurseries until the environmental self-management reaches the necessary scale to exercise the integral regenerative management of the basin. In addition, the model, once tested, will be transferable to other three ADI established in Mapuche ancestral territories, along with the learning and methods generated from within the Lafkenche territory of Lake Budi. Together with an interdisciplinary team in the territory, it will promote participation, associability and Lafkenche economic, cultural and socio-environmental self-governance in Lake Budi.

As a community enterprise, the Network will support associative marketing, which will allow associates to offer, in a sustainable manner, a crucial socio-environmental service to between 3 to 120 ADI communities: an offer of native and multipurpose trees (fruit trees and others of low water demand) at low cost—to be subsidized by sales at market prices to external customers—that will encourage their incorporation into small family groups.

Furthermore, as a policy creator, within the framework of the 5 ADIs established in the southern zone, the Network will demonstrate that support for the installation and incubation stages of community nursery networks can be effective, efficient, and with high impact, generating value for indigenous lands in addition to promoting environmental and economic self-management in these communities.

If you want to be part of this collaborative cross-cultural effort, you can contact us at maplemicrodevelopment.org or directly at alison.guzman@maplemicro.org or ignacio@maplemicro.org.

—

Since 2013, MAPLE’s interdisciplinary team, made up of co-directors Alison Guzmán (M.A..) and Ignacio Krell (M.A.) (for bios click here) and its more than 10 collaborators in 3 communities of Budi, has conducted co-design processes for tools of sustainable development and management in the areas of community micro-finance (Llaguipulli Mutual Support Group 2013, Bank of Materials for Artisans 2017), management of cultural assets (Joint project on Kuzao Zomo Entrepreneurs Association 2016), and environmental management (nurseries 2015, 2016, 2017, rainwater harvesting 2017, regenerative agroforestry and native berry orchards, soil and organic seeds recovery 2016, 2107, 2018). In the area of management of environmental assets, the team collaborates with actors involved with the issue of degradation and devaluation of indigenous environmental assets: the Municipality of T. Schmidt, CONAF, INIA Carillanca, Huelemu Experimental Center and Kennedy Foundation, with support from domestic sources (MMA - Indigenous Environmental Protection Fund 2015, 2016 and 2017) and international sources, such as International Foundation, Keepers of the Earth Fund, Indigenous Ways of Knowing and Learning Fund, The Bay and Paul Foundations, among others.

References

Departamento de Ciencias Ecológicas Facultad de Ciencias Universidad de Chile (2010) Análisis del Impacto Económico y Social y Objetivos de Calidad Ambiental del Lago Budi. Laboratorio de Modelación Ecológica, Santiago, Chile.

Flores, Juan P., Martínez, Eduardo (2010) Determinación de la erosión actual y potencial de los suelos de Chile. Publicación CIREN N°139. http://bibliotecadigital.ciren.cl/handle/123456789/2016

Mariola, Matthew J. (2018) Limited Fertility, Limited Land: Barriers to Sustainability in a Chilean Agrarian Community. In “Sustainability of Agroecosystems”. IntechOpen https://www.intechopen.com/books/sustainability-of-agroecosystems/limited-fertility-limited-land-barriers-to-sustainability-in-a-chilean-agrarian-community

Peña-Cortés, Fernando et al. (2006) Dinámica del paisaje para el período 1980-2004 en la cuenca costera del Lago Budi, Chile. Consideraciones para la conservación de sus humedales. Ecología Austral 16:183-196. http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1667-782X2006000200009

Universidad Mayor de Chile (2011) Documento de diagnóstico: Estudio de Riesgo y Actualización PRC de Saavedra. Temuco, Chile. http://www.observatoriopanamericano.org/WKP/RECURSOS/OTROS%20DOCUMENTOS/CHILE/INFORMES%20CH/Estudio%20de%20Riesgo%20y%20Actualizacio%CC%81n.pdf

Abbreviations

ADI- Area of Indigenous Development (Area de Desarrollo Indígena)

CONAF - National Forest Corporation (Corporación Nacional Forestal)

INIA - National Institute of Agricultural Research (Instituto Nacional de Investigación Agropecuaria)

MMA - Ministry of the Environment (Ministerio del Medio Ambiente)

SAG –Servicio Agrícola Ganadero